Education during COVID-19

The reality of virtual learning for young children

After her 12-hour night shift at Virginia Hospital Center, Melinda Campoverde, R.N. pulled her minivan into the garage and sent the garage doors rolling down behind her. After pausing to sanitize her phone, keys, and purse, she hopped down onto the concrete. Pulling off her scrubs and tossing them in a heap, she opened the door to the downstairs family room, and walked in, butt-naked. She proceeded directly to the shower.

Happy, high-pitched voices upstairs signaled that her young children, one of them school-age, were waking up. She greeted them with hugs and snuggles, then headed to bed. Her husband, or the children's aunt or grandmother would care for them for the next few hours while she slept.

When she awoke, her second job would begin: Schooling the 1st grader at home while keeping the younger ones occupied. She joined the ranks of parents struggling to work, care for little ones, and school their older kids, all at the same time.

At the beginning of the school shut down, Manassas Public Schools gave parents a simple list of resources to use while educating their children at home. No assignments were given no curriculum was offered and no online classes were provided. Since the coming months seemed completely uncertain, Melinda decided to register her children as bonafide homeschool students, an option which has always been available as an officially authorized alternative path. Ordering curriculum from the many online providers, she settled in to do school at home.

As an essential worker married to another essential worker, Melinda and her husband were among the group of parents who continued working just as they had before the COVID-19 pandemic. Except now, their kids were not at school but at home, needing all that had previously been done at school from their parents.

Fortunately, they were some of the lucky ones who had the family assistance and the ability to do work and educate their children at home.

Among all the other COVID-19 pandemic worries, parents had one additional issue: the choice between sending their children to school and risking infection, or keeping them home and allowing them to learn online. Many parents unfortunately lost their jobs in the pandemic and suffered financially, but were able to be home and assist with their learning.

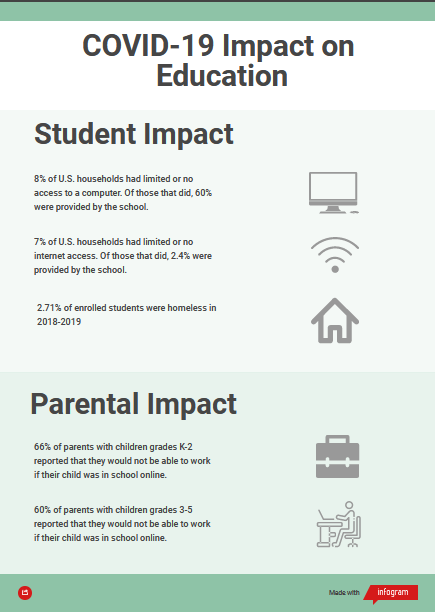

Other parents continued to work outside the home but were not able to help their children with their online schooling. Still other families did not have internet access at all, nor did they have a computer. Both of these situations have extreme down-sides, and parents were desperate for alternatives. Some creative minds stepped up to fill that void.

One option was developed out of the existing children’s activities program at the nZone, in Chantilly, Virginia.

The program was called Education Station and was developed by then assistant director Sarah Wells and the former director. Sarah Wells, who is now the Director of Youth Services, explained that Education Station was developed to fit a specific need that they saw spring up in the midst of the pandemic. The nZone is a large industrial space that was transformed into an indoor sports center, including soccer fields, restrooms, tables, chairs, and food service. This large space offered the room needed for kids to spread out in order to abide by covid safety protocols, while also being in a social environment.

The CDC recommends that childcare centers divide their children into small groups or “cohorts” and be assigned one teacher for the whole year. These cohorts are to interact as minimally as possible. Within each cohort, social distancing should still be practiced indoors. They recommend using physical dividers between each student, and to stagger lunch times between cohorts.

The nZone was able to apply these guidelines, using the basketball court as a makeshift classroom. Homeschooled, hybrid, or online-only students ages 5-14 come to the program for any amount of time between 7 am and 5 pm. Small groups sit on opposite sides of the spacious room at tables with dividers separating the children as they work on their schoolwork. Each group is assigned an educational aide who helps the students stay on track and gives them any support or extra help they may need. The best part of the school day is when the kids go outside and play field games, getting a much needed break and time to have fun with friends. “we were able to help out so many families, providing relief to parents so they can carry on with their jobs, giving kids the support and encouragement they need in the classroom, and providing them excitement on the field, as well as a much needed brain break”.

Education Station has been able to provide the support and co-teaching to students that is arguably crucial for educational success. Essential workers that are not able to educate their children at home can keep their kids in the same school environment, providing stability, while also ensuring they have the in-person support they need.

Other families have not been so lucky. Many low-income families are not able to pay for programs to send their kids to while they work, and do not have the time or ability to teach their kids at home.

Bellwether education partners, a nonprofit focused on changing education outcomes of underserved communities, found that as much as 3 million students were not attending school due to lack of resources to participate in the online environment. A back-to-school family survey in Washington DC found that 60% of students did not have the devices necessary to participate in online schooling. 27% of the students did not have adequate internet. The phenomenon of children disappearing from the education system has been observed by kindergarten teacher Elissa Fielder.

Listen to Elissa’s perspective

Elissa Fielder is a kindergarten teacher for Hawaii Public Schools, with a background in education policy and a master in elementary education from Johns Hopkins University. She became a kindergarten teacher through Teach for America, a competitive program that prepares young people to teach in low-income school systems.

Elissa had to adapt very quickly to a new way of teaching her kids online. She began the 2019-2020 school year with 15 kids many of whom were English language learners and were moderately struggling. When schools closed in March 2020, many of these kids did not have parents at home who were available to assist them with their online classes, and if they did, the parents struggled with both the technology and the teaching. Some homes did not have computers or internet access. Elissa’s class size quickly dwindled to 7 kids, all of whom were lucky enough to have parents that were able to be involved.

By the time that Elissa had figured out the best way to teach online and had gotten very good at it, it was too late. Half of the kids in her classroom had disappeared, had fallen off the grid of the education system. Elissa called, sent postal mail, and tried to visit some homes in person, to encourage parents to re engage their children in education, and assist them with any technical issues they may have.

Elissa explains how crucial adult involvement is in the virtual environment. “Kindergarteners are still developing the skill of copying. Just to show them the letter doesn’t necessarily work, you have to take their hands and put them where they need to go”. Parents were still needed as co-teachers. Many parents just did not know how to be co-teachers, or were not available to do so. By the time school was back in person, these kids that had been absent from online classes were back to square one in terms of learning. They did not know a single letter. They had to relearn everything.

COVID-19 brought out the best in a lot of people. It caused people to come together and find creative solutions to the issues involving educating young kids during the lockdowns. Daycares, gyms, and other facilities were turned into learning centers. Public schools stepped up to gather the resources to teach virtually in the best way. Many mothers found homeschooling to be a positive thing for their family. Melinda Campoverde noted that the pandemic brought her family closer. Unfortunately, many families were still left behind. The earnest efforts to reach out to these disadvantaged families and offer resources were more often than not unsuccessful.